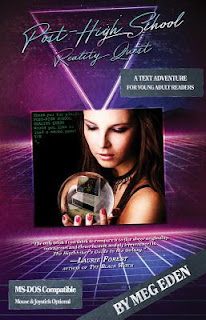

Post-High School Reality Quest is a unique take on the transition that happens after high school. Gamers who love quest games (and even those who are not!) will appreciate classic elements written into a book that explores the journey from teen to adulthood and all of the complications that follow. Fans of At the Edge of the Universe will love this!

Post-High School Reality Quest is a unique tale, and I was curious about Meg’s research and writing process. Check out her guest post on why games make her want to write!

Time Travel, Text Parsers, and Coping With Change: Why Games Make Me Want to Write

I watch a lot of Let’s Plays, that is—videos of other people playing video games. This might be because before my cousin got his N64 (and even sometimes after) I was the girl who “watched games” because I was a girl and I “wouldn’t understand how to play.” I hated that my cousin said this because well, it was false and also gloriously ironic, considering he kept dying in the same places on the same maps. But I’ve come to really enjoy watching and dissecting games, the way a linguist dissects and observes languages and how they function on a larger level. A linguist doesn’t know a million languages but knows how they work. Likewise, I don’t necessarily know a million games, but I enjoy seeing how they work, and how I can learn from games in writing my own stories.

I started rewriting my novel Post-High School Reality Quest (PHSRQ) in its current form during a series of strep episodes. I was tired and bed-ridden and not really feeling like doing anything except writing and playing video games. My friend joked one day that I should write a novel in the form of a text adventure. During one of my strep bouts, I tried this and couldn’t stop. I think once I started playing with the text adventure format, writing felt like playing a video game, which kept me distracted and amused during my bouts of strep.

The ironic thing is that my introduction to text adventures wasn’t actual…text adventures. But it was through playing games, and particularly through a translation of text adventures: the live Parsley games. What is really interesting about the Parsley games is that they are interactive, live-action text adventure games. One person plays the text parser, and the rest of the people play as players, inputting commands. My friends in high school loved these Parsley games. A few of my friends were on the improv team and loved playing the text parser, coming up with clever responses to absurd commands. What’s really fun and interesting about these is that the person who plays the text parser is kind of like a DM in Dungeons & Dragons—they really set the tone and environment of the game. We’d all make the most absurd inputs we could and the text parsers would have a lot of fun messing with us. While games can imitate personality (I think of the snarky narrator from Stanley Parable), but that specificity in response and level of interactivity is only something that can happen with real people.

But this juxtaposition of human and game really interested me, and certainly influenced how I approached writing the text parser in PHSRQ. I wasn’t limited by the idea of a conventional text parser, but really opened up how I viewed this character—because really, the text parser is a character in PHSRQ, not just a mechanism for narration. The interactions between the text parser and Buffy became the plot and tension of the novel. Since I’m terrible at plot, this really helped PHSRQ become what it is now.

Another structure from games that has really influenced my writing is the idea of pacing and time. I’m really fascinated by ideas of time travel—not just literally (which games like Ghost Trick and Life is Strange play with) but even more so, mentally (think Miss Havingsham from Great Expectations in her decaying wedding gown, unable to move forward from being jilted at the alter). I love games that allow me to play the same thing over and over again. I’ll play Splatoon for hours, painting the same maps over and over again and find great satisfaction in that. I play Fire Emblem on casual mode, but even so restart a map anytime someone dies. I bookmark everything (an absent feature that makes playing Shadows of Valencia all the more intense) so I can play a map over and over until I get the outcome I want. This idea of playing and re-playing really fascinates me, and continues to come up in my writing, particularly PHSRQ.

I’m sometimes asked which games inspired PHSRQ, but as I think about it, I don’t think I was influenced by any specific game as much as I was by what games are—or maybe more accurately, what I think of and remember games as. My introduction to gaming was through playing with my cousin on the weekends. Those same weekends, we’d explore the woods and build forts. Playing games reminds me of the past, and makes me feel a false sense of being able to control time and pacing, going back to being that kid in the woods. In a game, I can restart a game, or if I’m not ready to go onto the boss battle, I can grind and level up my Pokémon or my Fire Emblem army. No one makes me progress forward until I’m ready. We often look back at big milestone times in our life, like college and high school, and wonder what our play-through would look like if we made different choices. We wish we could go back and replay the same encounter over and over until we find the right thing to say, or to go back to a place that now no longer exists. Unfortunately life doesn’t come with save slots. The act of writing, however, allows us to relive experiences and process stories at our own pace. For me, writing is like constantly playing a game of my own design, and when it’s been edited and cleaned up, I feel like I’ve hit 100% completion and am ready to move onto the next game.

Post-High School Reality Quest

Post-High School Reality Quest

by Meg Eden

Published: June 13th 2017

Publisher: Rare Bird Books

Source: Publisher

Find It

Buffy is playing a game. However, the game is her life, and there are no instructions or cheat codes on how to win.

After graduating high school, a voice called “the text parser” emerges in Buffy’s head, narrating her life as a classic text adventure game. Buffy figures this is just a manifestation of her shy, awkward, nerdy nature—until the voice doesn’t go away, and instead begins to dominate her thoughts, telling her how to life her life. Though Buffy tries to beat the game, crash it, and even restart it, it becomes clear that this game is not something she can simply “shut off” or beat without the text parser’s help.

While the text parser tries to give Buffy advice on how “to win the game,” Buffy decides to pursue her own game-plan: start over, make new friends, and win her long-time crush Tristan’s heart. But even when Buffy gets the guy of her dreams, the game doesn’t stop. In fact, it gets worse than she could’ve ever imagined: her crumbling group of friends fall apart, her roommate turns against her, and Buffy finds herself trying to survive in a game built off her greatest nightmares.